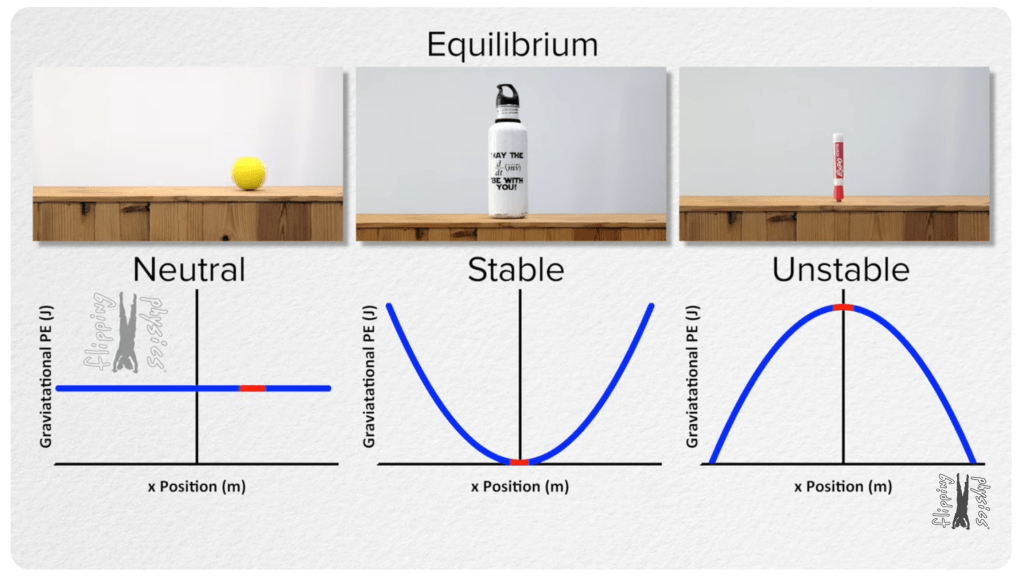

Neutral vs. Stable vs. Unstable

Let’s start by clarifying the three kinds of equilibrium: (Refer to the below photo/video)

- Neutral: The object stays put when moved (like a ball on a flat surface).

- Stable: The object returns to the center after being nudged (like a standing water bottle).

- Unstable: The object easily tips over (like a standing marker).

ref: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4rG9u478X1Q

Now, take a look at what stability means on an aircraft:

Aircraft stability is the inherent ability of an aircraft to maintain or naturally return to its original flight attitude or path following a disturbance, such as a wind gust or a control input. Same as above, aircraft stability is categorized as positive (returns to equilibrium), neutral (stays in the new state), or negative (diverges further).

An example of this concept along the airplane’s lateral axis is pitch stability (or longitudinal stability). See a diagram below:

Quick Q&A:

Can an aircraft fly with neutral stability? Answer. It’s possible, but incredibly hard for the pilot!

How about flying with an inherently unstable aircraft or helicopter?

The short answer is: no, not manually. An aircraft with negative (unstable) stability requires constant, immediate correction. To make such an unstable design fly, it must be equipped with a stability-enhancing system—such as fly-by-wire or a gyroscopic system—like those found on all modern drones.

In short, for an aircraft to maintain flight without constant manual input (i.e., hands-free operation), it must possess positive stability across all three axes (pitch, roll, and yaw).

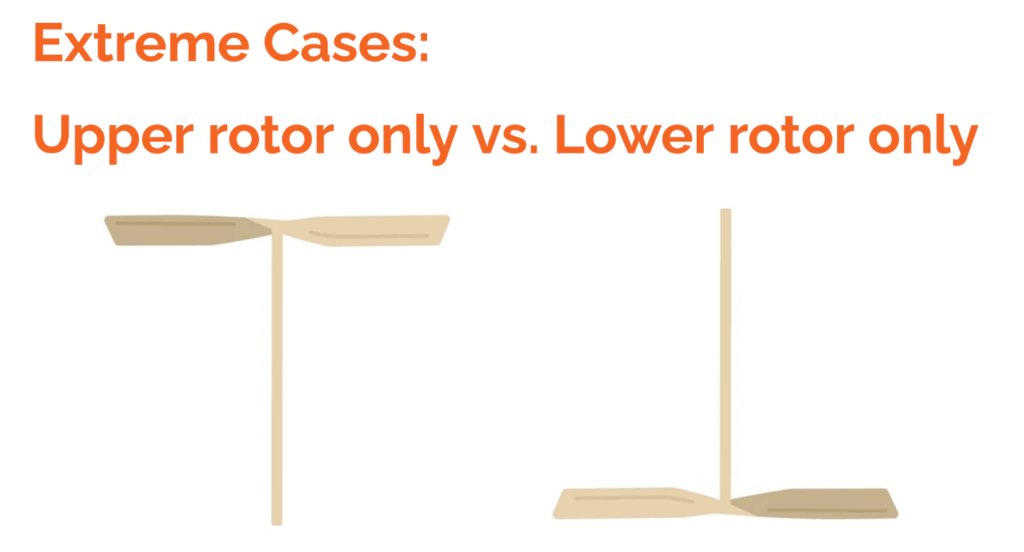

Unstable Helicopter vs. Stable Helicopter

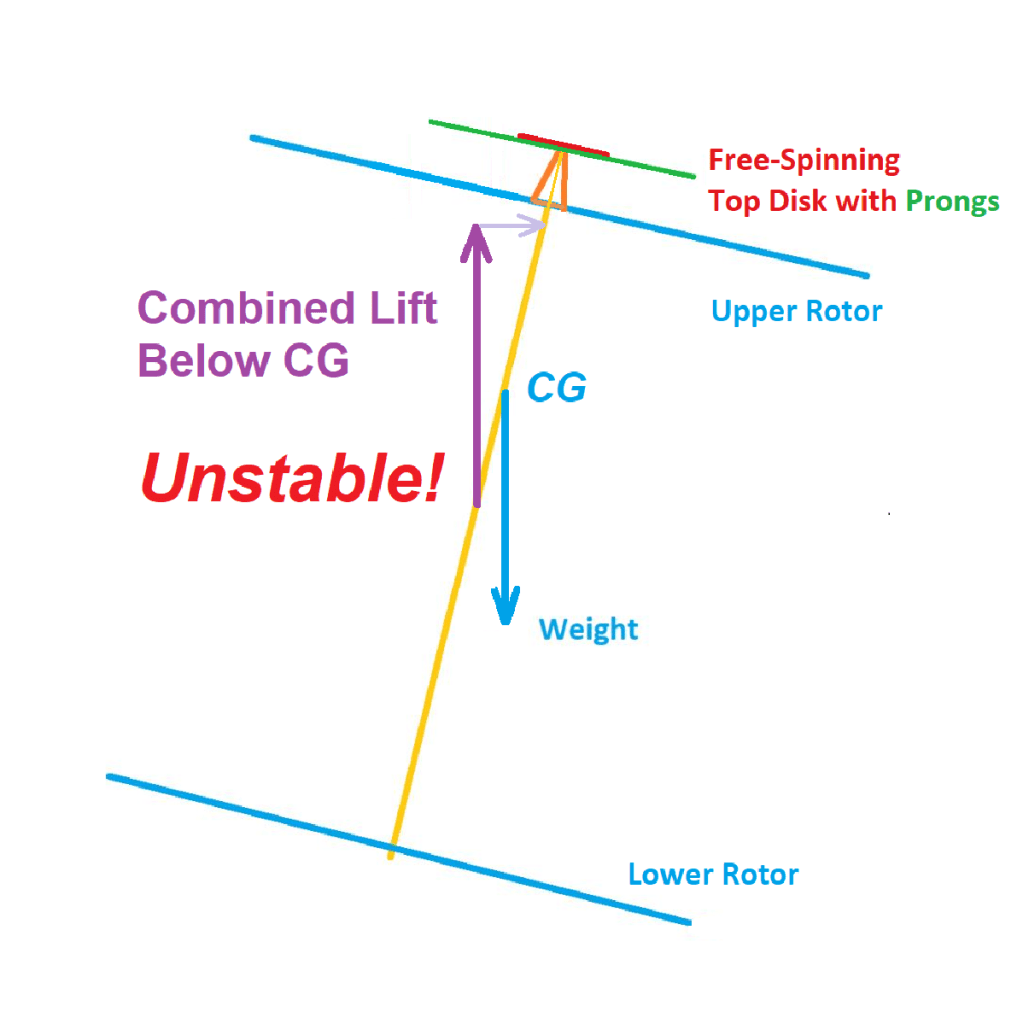

Here is one easy way to demonstrate a helicopter with negative stability. Pick up a bamboo toy helicopter and fly it upside down. (See the right side of the slide below.) It’s impossible, right?! This demonstration explains why a bottom-rotor-only helicopter design is almost non-existent. It is unstable!

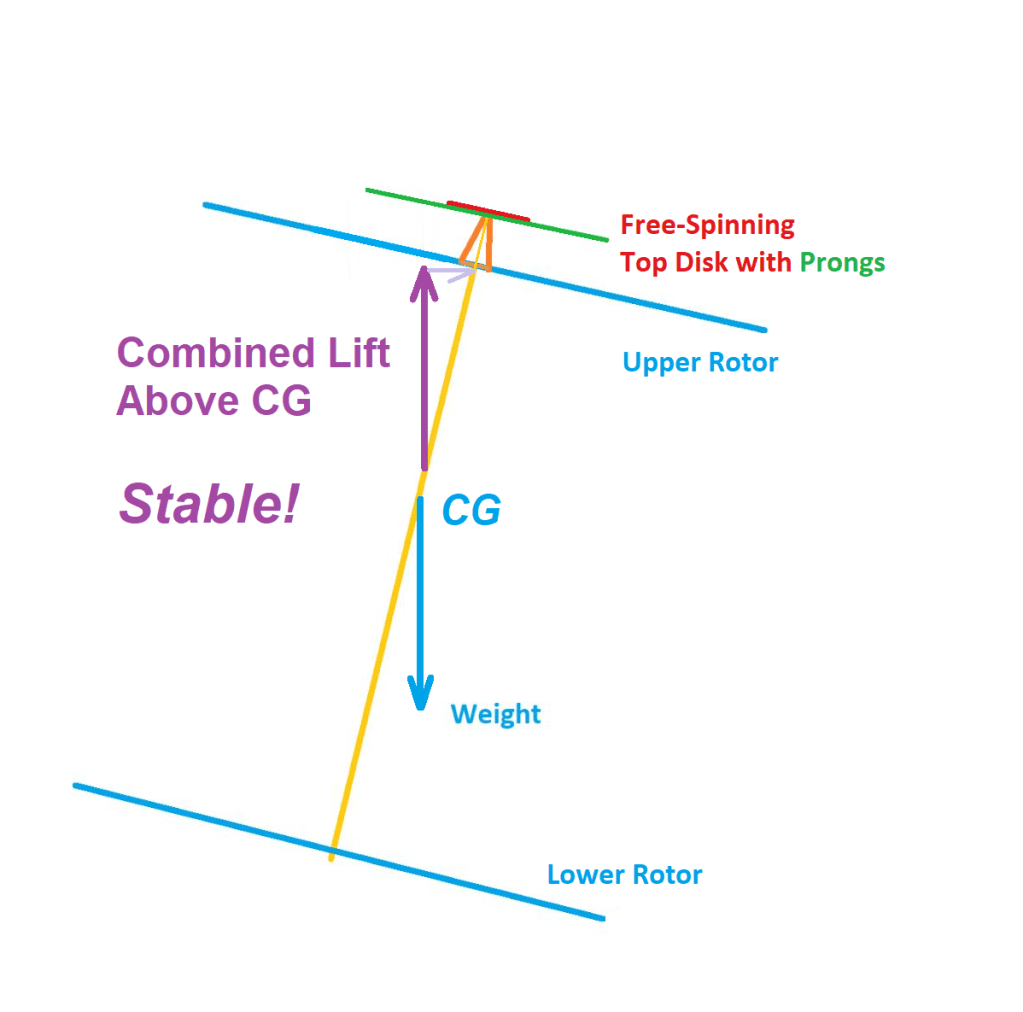

Now, let’s look at a normal, right-side-up toy helicopter on the left above. Its positive stability comes from the pendulum effect: the center of the Lift generated by the top rotor is clearly above the helicopter’s center of gravity (CG). This setup works like a pendulum, naturally wanting to return to a stable, upright position. The next two sketches below illustrate this principle for a common coaxial SO helicopter.

Note to all builders: Be sure not to over build the top free-spinning disk tower on our SO Helicopter. A heavy top tower (and/or a top vane) may raise the CG too high and result in an unstable helicopter that can never reach the ceiling.

Viper25 Helicopter Stability:

In addition to using a light top disk tower, my Viper25 design utilized a unique differential-lift feature to ensure positive stability: the upper rotor had a lower pitch than the bottom one. This design choice allowed the upper rotor to spin faster (higher revolutions per second) and generate more lift. The goal of this differential lift setup was to ensure the combined lifting center stays above the Center of Gravity (CG), resulting in positive stability.

A side note, the Viper25 ended up with too great a pitch difference, making it too stable. To improve, the lower rotor’s pitch was reduced for better efficiency and longer flight time.

For comparison, four-blade top rotor setups (like those seen on many modern 2025 helicopters) generally generate extra lift simply by having a greater total blade area. While this is a simplified view -a full analysis requires examining the Lift and Drag equations and CL-CD curves for both rotors- we will cover the numerous design trade-offs between two- and four-blade helicopters in a future discussion.

A quick note on dihedral: While increasing the dihedral (upward angle) of an airplane’s main wing is a common practice for boosting its lateral stability, this technique is risky for our SO helicopters. Adding dihedral to a rotor blade creates elevated blade tips that could scrape the ceiling. This contact would adversely cause our helicopter to swirl or wobble, or potentially strike something and damage the blades.

Additionally, tilting up the blade tip not only unnecessarily increases the build complexity, it also increases the rotor’s side area. This extra side area creates a significant drawback. (Same as adding a top vane), any increased side area on top adversely boosts the risk of the craft being blown away by air currents, as explained in my previous article. For these reasons, I do not recommend purposely tilting up the blade tips on a SO helicopter. A properly designed differential-lift, i.e. pendulum effect, is sufficient for an indoor free flight SO helicopter to stay stable.

In summary, to build a stable and flyable coaxial helicopter, we must ensure the upper rotor generates more lift than the lower rotor, placing the combined center of lift above the Center of Gravity (CG).

Next up, we will discuss Rocket stability (or moving object stability). This is highly relevant to the SO helicopter, as it needs a positive rocket stability to move through the air, to reach the ceiling and to descend reliably, in order to maximize flight time. We will investigate how some common features, such as a top vane, affect this crucial rocket stability.

Stay tuned!

-AeroMartin 10/25/2025

Leave a comment