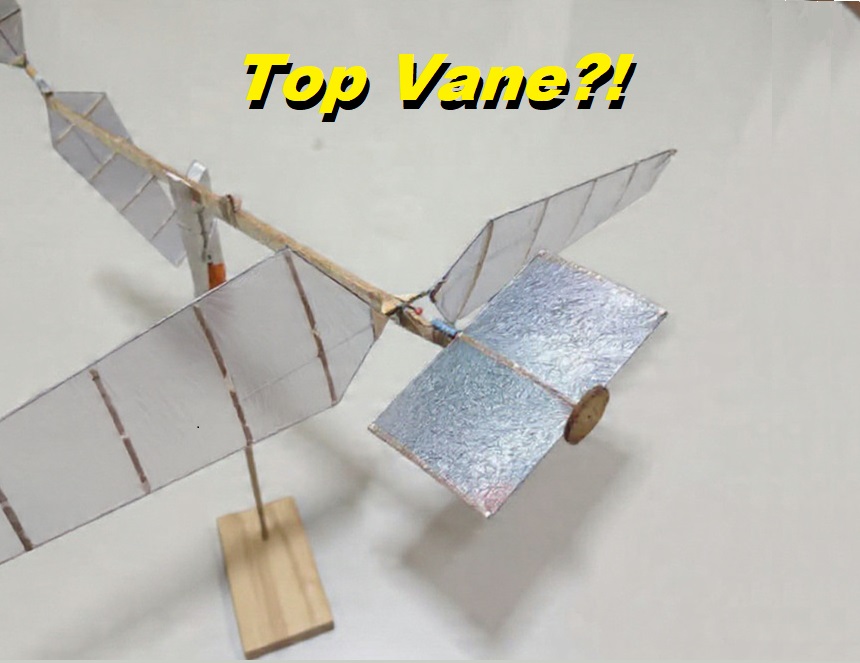

The short answer is that the top vane mostly hurts stability, especially when the helicopter needs it most! It causes problems during the critical Ascent and Ceiling phases, offering only a small benefit during the brief Descent.

The Wind Vane and Rocket Stability

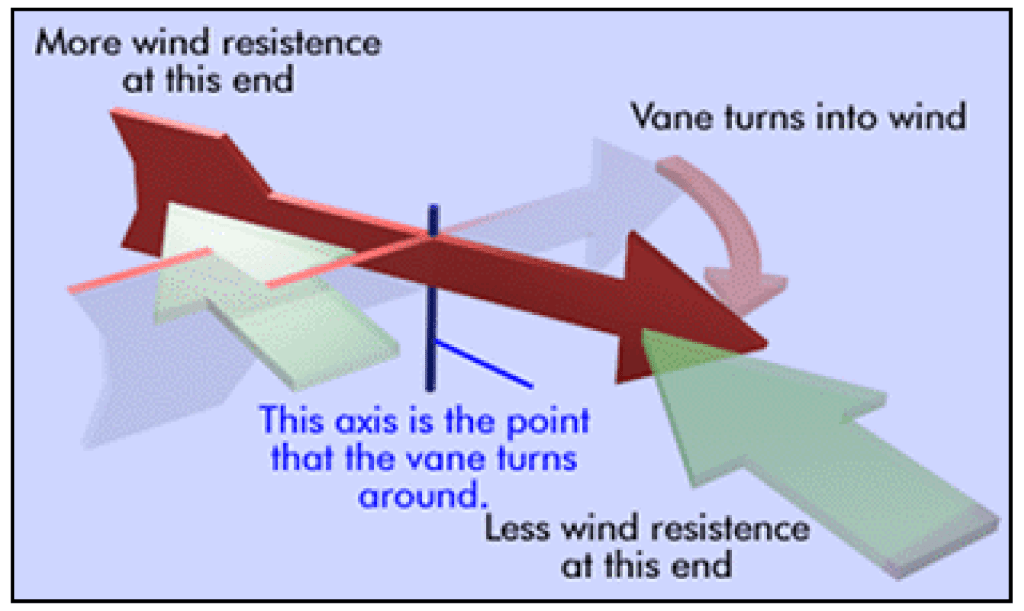

Let’s start with a fundamental concept, weather cocking. See a diagram below.

Think about a common wind vane on a roof. It has a large tail that always points downwind (away from the wind). Why? Because the moving wind pushes on that large tail, causing it to pivot around a central rod until the tail is behind the center.

Just as the feathers on an arrow keep the tip pointing forward, the aerodynamic forces will ensure the Center of Pressure (CP) is always kept behind the Center of Gravity (CG) relative to the direction of motion. This relationship between CG and CP is the foundation of Rocket Stability.

Ref: https://www1.grc.nasa.gov/beginners-guide-to-aeronautics/rocket-stability/

The Top Vane’s Problematic Effects

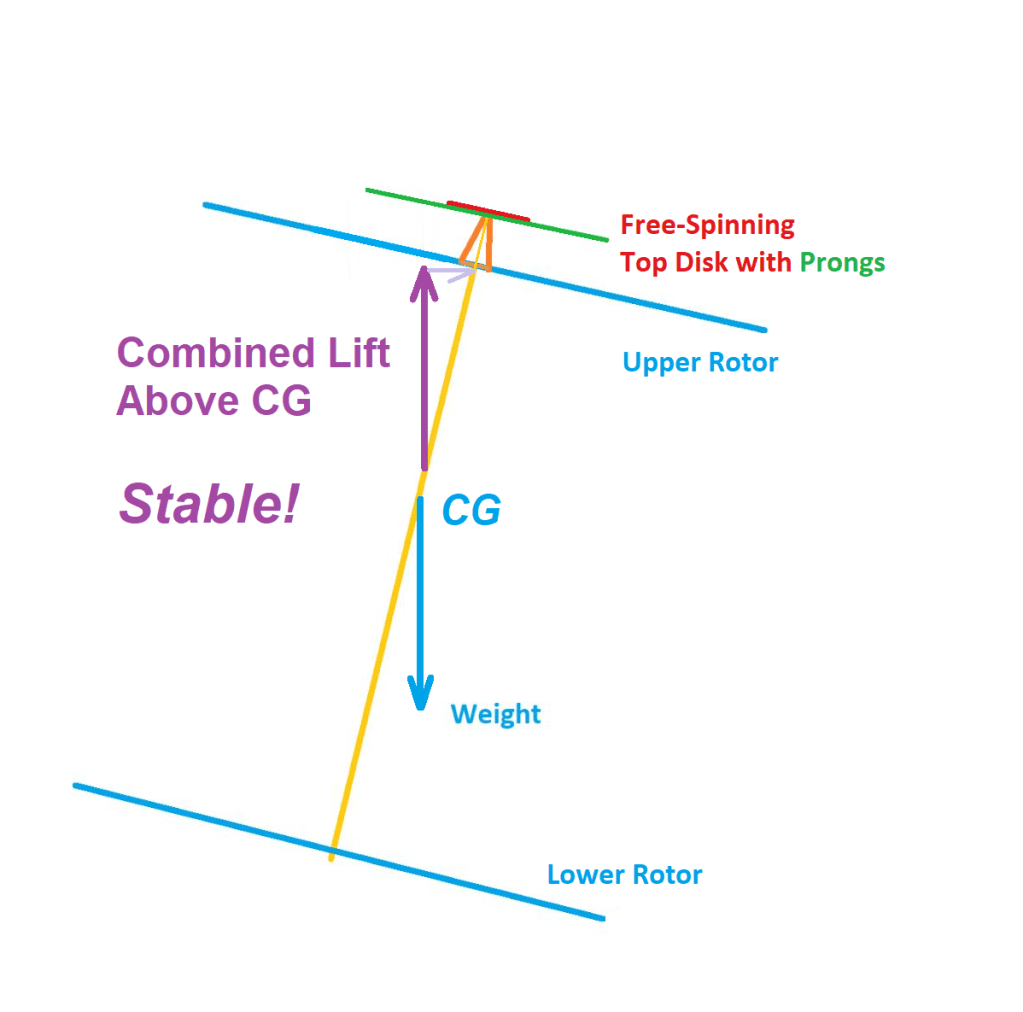

Now let’s list out how a top vane, which shifts the CP of a typical SO coaxial helicopter upward and above CG, would affect the stability during three different phases of our SO helicopter.

| Flight Phase | Vane’s Effect | Stability Outcome |

| Vertical Ascent | The vane/large top area causes the CP to be ahead of the CG (unstable configuration). | Hurts Stability. Leads to “wild” launches, especially at high speed. |

| Under the ceiling with Horizontal Air Currents | The vane increases the top side area, pushing the CP higher than the CG. | Hurts Stability. Any horizontal current pushes the helicopter away easily. |

| Descent | With the movement direction reversed, the CP is now behind (above) the CG (stable configuration). | Helps Stability. This is its only positive role. |

As highlighted above, the vane’s sole contribution to stability is during the short descent, but this benefit is easily achieved without a vane by using a larger lifting area, such as a four-blade top rotor to keep the Center of Pressure (CP) high. (Or, by adding dihedral on the top rotor. However, there are problems with dihedral. See my previous post here.)

Moreover, adding any weight high up on the motor stick—such as a top vane—risks raising the Center of Gravity (CG) too high. A high CG will severely derail stability during the crucial ascent phase, potentially making the helicopter un-flyable.

Conclusion: The Top Vane Isn’t Worth It

The vane’s two major drawbacks—destabilizing the critical ascent and increasing susceptibility to side-winds—far outweigh its single, fleeting benefit during descent.

Better Stability Solutions

Focus on a Low CG (The Pendulum Effect): This is the single most effective way to ensure stability. By keeping the CG low, the combined lift vector constantly acts to pull the helicopter back to vertical, much like a pendulum. A top rotor with more blades can often achieve the same stable descent without the extra weight and wind-catching surface of a top vane. For those who follow the KISS principle and prefer two-blade design, you can still effectively improve stability by using differential lift, a feature found in designs like the Viper25 helicopter.

Final Thought: Design is a Compromise

Any design is a compromise. Because our SO helicopters have to go through the two opposite ascending and descending directions, one of those two will inevitably result in a CP ahead of CG unstable arrangement. The cure?! Fly slowly. The destabilizing force from the CP is directly related to a helicopter’s moving speed. By flying at a reduced speed, one would dramatically lessen the effect of the unstable CP/CG configuration and avoid wild unstable maneuvers. Besides, flying slowly and maintaining low rps (Revolutions Per Second), is the key to the longest flight. We will chat about that topic in a future discussion.

Stay tuned!

-AeroMartin 10/31/2025

Leave a comment