Fly slow! But not too slow!

How slow should a SO aircraft fly? How slow should a SO helicopter rotor rotate?

And,

Why slower, not faster!?

These are crucial questions. Ever since I began coaching SO Flight events, I have consistently instructed my teams to trim their aircraft for an effective slower flight speed.

Flying fast results in short duration and dramatically increases the risk of disaster, particularly when a new, powerful rubber motor is installed. While a strong motor can force even a poorly-built aircraft into the air, it will fly fast and finish its flight quickly. Such rapid ascents often lead to immediate catastrophic failures: the airplane may shoot up and smash into a wall, or the helicopter may violently impact the ceiling and unkit itself. Flying at the correct, slower speed is the single most effective way to prevent these competition-ending mishaps and achieve the longest flight duration.

Glider Principles: The Minimum Sink Rate

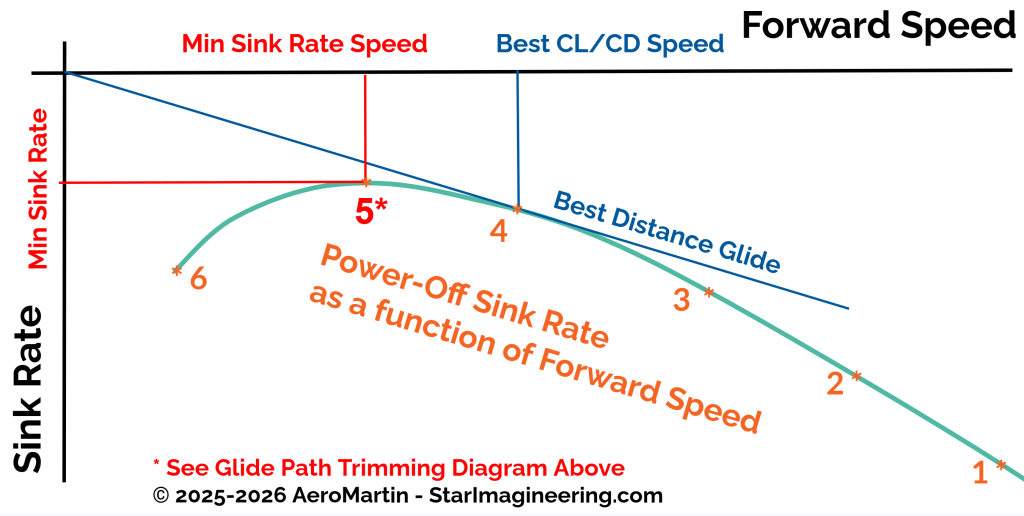

To determine the optimal speed for maximizing flight duration, we begin with the glider. I have illustrated this best speed in two diagrams, originally drawn for the 2013-2014 Glider event. I have referenced these diagrams several times since, including at the 2023 Summer Workshop at SoCal. See them below.

A glider, having a set amount of potential energy from its launch height, must maximize the time it takes to descend. The SO Flight event is judged strictly on duration.

First, we must distinguish our goal: If the goal were to maximize distance (or range), we would trim for the fastest, most efficient speed, which corresponds to the best Lift-to-Drag ratio, (L/D)max. Since the SO Flight event is strictly focused on duration, we must instead aim for the speed that minimizes the sink rate. This concept can be also visualized by plotting the glider’s sink rate against its forward flight speed. (See below for a generic plot.) With this plot, we can clearly see that the target speed, VminSinkRate, is slower than the speed for best Lift-to-Drag that achieves the farthest distance, VbestSpeed.

Quantitatively, VminSinkRate is typically about 0.76 times the speed for best Lift-to-Drag, VbestSpeed.

To maximize flight time, the glider must fly at this significantly slower speed: VminSinkRate. Flying at VminSinkRate ensures the glider loses altitude at the slowest possible rate, thereby guaranteeing the maximum time in the air. This is the foundational principle for many indoor free flight competitions.

Controlling Angle of Attack (AOA) for Optimal Speed

We have now identified the speed we want, but how do we actually control that speed in flight? While flight speed is primarily determined by the Angle of Attack (AOA), we as flyers have no direct control over this angle during flight.

Our practical controls at the flying field are the Center of Gravity (CG) location and the tail trim. At the design phase, we can manipulate other parameters, such as the wing’s Incidence and the selection of different airfoils.

We use these adjustments to set the overall aircraft balance and force the wing to fly at the specific AOA required for the optimal speed, VminSinkRate. As illustrated above, this VminSinkRate is significantly slower, and therefore occurs at a large AOA. This target AOA is close to, but less than, the stalling AOA. Achieving this perfect trim setting, and thus the perfect slow-but-not-too-slow speed, requires extensive trial-and-error during test flights.

Helicopter Rotor: The Minimum Power Strategy

Minimum sink rate for a glider indicates the minimal rate of losing potential energy. The rate of energy change equals power; Power (P) = Change in Energy (ΔE) / Change in Time (Δt), Therefore, maximizing flight time means trimming the glider to fly at the speed that requires the minimum power to sustain flight.

This principle applies directly to the helicopter rotor: a rotor blade is simply a wing flying in a circle, and the rotor must rotate at a speed that demands minimum power. Similar to the glider discussion above, this requirement translates directly into finding the optimal slower rotational speed, RPS, for the rotor.

By adjusting both the pitch of the rotor blades (which governs the AOA) and the rubber motor’s size/density, which governs the torque, we force the rotor to spin at the ideal, slow rate. This ensures the potential energy stored in the rubber motor is unwound as slowly as possible, maximizing the total flight time.

Conclusion: The Minimum Power Mandate

The success of any Science Olympiad flight event hinges on one principle: Minimum Power Required.

- For the airplane event, this minimum power is achieved by setting the aircraft’s trim to force the wing to fly at the Minimum Sink Rate speed.

- For the helicopter event, this minimum power is achieved by trimming the rotor blades to spin at the specific optimal slow RPS.

There you have it: the secret to winning SO Flight! Watch below to see just how slowly the fifteen 2023 Workshop Apache24s airplanes flew, and the Viper25’s first attempt at slowing its rotors

Is your SO helicopter or airplane flying too fast? Post or send a video of your flight, and many experienced coaches online will be happy to guide you in trimming for that crucial “slow-but-not-too-slow” speed.

Cheers!

-AeroMartin 12/15/2025

Leave a reply to AeroMartin Cancel reply